Microinsurance is a part of the insurance continuum, with products that feature pricing, coverage and distribution that are designed to be appropriate for low-income customers. By that definition, microinsurance is relevant to around 50% of the world’s population and up to 80% in some countries, making it impossible to ignore in an emerging economy. Over time, microinsurance has been called by different names — inclusive insurance, and emerging consumer insurance to name a few. However, at the core, they are all mechanisms to protect low-income people against risk.

Since commercial microinsurance entered the scene in the late 1990s, multinational and domestic insurers have tried their hand at delivering products to low-income customers. While some succeeded by understanding and catering to the specific needs of this segment, others floundered. There were many barriers to success: difficulty in reaching customers, a lack of cost-effective distribution channels and appropriate regulations — which are key to achieving sustained growth. However, recent developments especially in the digital space have made it easier for insurers to cater to the low-income segment effectively.

Today almost all low-income customers have access to a feature phone, if not a smartphone, making it relatively easy to reach them. The rise of customer tech platforms that aggregate low-income populations as service providers (ride-hailing apps) or as customers (remittance platforms), serve as efficient distribution points. Insurtechs, even those catering to low-income customers, have evolved their business models to offer plug-and-play solutions to insurers. Meanwhile, regulators are setting up sandboxes to allow experimentation and redesigning microinsurance regulations to keep up with the times. All these developments have made it an opportune time for mainstream insurers to focus on the microinsurance opportunity.

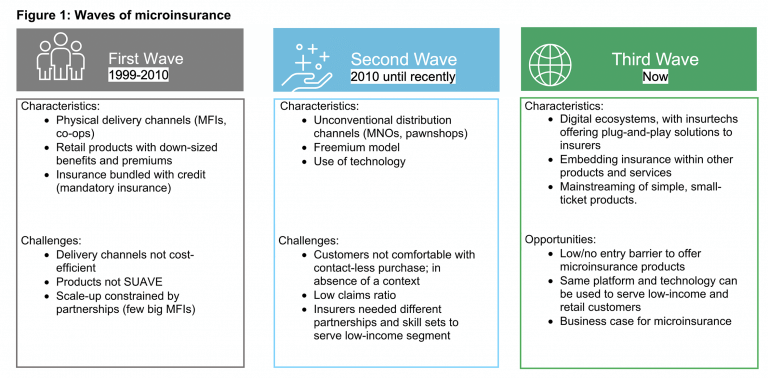

This is the third wave of microinsurance. It is driven by digital platforms, embedded insurance and cross-benefits from mainstream insurers moving towards simple, small-ticket products. Let us first see how we got here.

First wave: Emerging from microfinance (1999-2010)

While microinsurance has been in existence for a long time, commercial insurers have pursued it since the mid-1990s. In this first wave, we saw microinsurance emerge out of the shadows of microfinance and develop into a sector of its own. Insurance was mostly sold through microfinance institutions (MFIs) by bundling it with loans. Clients didn’t get much value from these credit linked insurance products, because they primarily de-risked the lenders. Additionally, manual processes and physical channels of delivery made it tough for insurers to achieve cost efficiency. Insurers trialed products by downsizing the benefits and premiums of their retail products, causing them to fail.

Some of these setbacks highlighted the need to understand the specific needs of low-income customers and how best to serve them. A few organisations that wanted to promote and support the establishment of responsible microinsurance were set up during this time. The first of its kind was the MicroInsurance Centre, founded by Michael J. McCord with a mission to get “Simple, Understood, Accessible, Valuable and Efficient” (SUAVE) microinsurance in the hands of 3 billion low-income people. The SUAVE principle continues to be an established standard in microinsurance.

Second wave: Use of technology and unconventional distribution (2010 until recently)

The second wave of microinsurance was characterised by the use of technology as well as the development of unconventional distribution channels such as mobile network operators (MNOs), churches, supermarkets and pawnshops. Companies such as Bima and MicroEnsure used mobile technology and partnered with major telecommunications companies to provide microinsurance to low-income customers. Customers could enroll and register their insurance using feature phones via unstructured supplementary service data (USSD) and receive payouts via mobile money services. The assumption was that customers would receive free insurance (with premiums initially being paid by the MNOs) and then proactively upgrade to paid policies (the “freemium” model).

However, awareness about the products remained low, leading to low claims ratios. Additionally, because customers did not expect their MNOs to offer insurance products, they hesitated to upgrade unless they spoke to a company representative.

Philippines based insurer Pioneer, selling microinsurance through pawnshops and MFIs, took a different route to scale. They saw a dramatic uptake of policies once they focused on paying claims. They wanted to be known as “the insurer that pays claims,” because they viewed claim settlement, even in borderline cases, as an investment in marketing. While this seems like a simple and effective strategy to adopt, there are very few like Pioneer in the microinsurance space even today. Low claims ratios continue to challenge the sector, primarily due to lack of awareness among customers.

The second wave also saw many mainstream insurers set up microinsurance channels, departments and even standalone units, because they saw the promise in the idea that “today’s low-income are tomorrow’s middle class.”

Third wave: Digital transformation, embedded insurance and a mass movement towards simple, small-ticket products

The changes over the last few years have helped make it easier for an insurer to pursue the microinsurance opportunities. Three key developments in particular are noteworthy.

The first is digital transformation. Insurers, distribution partners and even low-income customers are going digital. Insurers across the spectrum, who were the last frontier of pen and paper-based business, have embarked on digital transformation with zeal. This is making it easier for them to collaborate effectively with insurtechs offering plug-and-play solutions, reducing the entry barrier for commercial insurers to add microinsurance to their portfolio. Add to this equation distribution partners such as digital platforms that employ gig workers or remittance platforms for migrant workers, and you have an entire ecosystem that can design and distribute insurance to low-income populations digitally.

The coalescence of these three factors (digital insurers, evolving insurtechs and digital distribution channels) could enable insurers to serve large, existing groups of low-income populations with an end-to-end digital journey, enabling true cost efficiencies. However, ensuring customer awareness and offering relevant value propositions will be crucial. This is where the next development comes in.

The second key development is the emergence of the embedded (integrated) insurance model. The embedded insurance model bundles insurance coverage within the sale of another product, service or platform—typically with a clear link within a context of risk management. This means the insurance product is not sold to the customer as a standalone purchase, but is instead provided as a built-in feature or option. Consider Lumkani, a social enterprise with a mission to mitigate the loss of life and property caused by slum fires in South Africa.

To accomplish this, Lumkani has developed and distributed networked early warning fire detection systems to homes in informal settlements across South Africa. Each fire alarm system comes with a household insurance against fire, which the customers can choose to add on. Another example could be insuring remittances sent home by migrant workers, such that future remittances would be made by the insurer in case of events such as death or job loss; or a ride hailing service insuring both the driver and the customer against the risk of accidents.

In each of these cases, there is a risk linkage (purchase of a fire detector of course conjures up thoughts of loss due to fire; making a remittance makes people think of what would happen to their families if they lose that income flow, and taking a hailed ride could indeed lead to an accident). This tight integration of insurance with another product, service or platform and the context of a sale reduces the friction that comes with “selling” insurance. Linkage of insurance to the context also ensures that customers are aware of being insured and will remember it. As long as the products are SUAVE, minimal customer education would be required.

The third key development that is positively affecting microinsurance is the mainstreaming of simple, small-ticket products. Insurtechs such as Lemonade started this movement a few years ago, in a bid to reimagine insurance and make it simple and accessible to all. Today, mainstream insurers are joining in and these simple, small-ticket policies are becoming a rage especially with the ‘millennial generation,’ who want to insure their cameras, flights or even marathons against risks of damage, delay and accidents. Interestingly, the two main characteristics of microinsurance—keeping it simple so that products are easy to explain, and charging small, well-timed premiums so low-income customers can afford it—are being used to attract new customer segments who are not low-income.

What this has done, though, is help even more mainstream insurers and insurtechs crack the formula of making small-ticket policies profitable. Because similar approaches are required to make microinsurance viable, cracking this formula will enable insurers to also serve low-income customers profitably. If there is a business case for micro-moment insurance, surely there should be a business case for microinsurance?

In conclusion, the third wave of microinsurance has made it easier for insurers to add microinsurance to their portfolios. There are lower barriers to entry and greater efficiencies. It is an opportunity to increase revenue and penetrate new markets, providing a competitive advantage and an avenue of profitable growth. The third wave promises to be an exciting time for the microinsurance sector because of the likely transformative use of technology to achieve greater good.

This article was written by Indira Gopalakrishna, a microinsurance specialist, Asia Pacific at Milliman.

-

Cybersecurity: The false promise of flawed certifications

- April 23

There is little correlation between certifications and avoiding breaches as the cybersecurity landscape evolves too quickly for annual checkups to be sufficient.

-

Trade credit: Amid trade war, APAC firms must stay agile and ensure adequate protection

- April 2

The US has implemented a new tariff regime across industries and countries, with import duties being a central aspect of US economic and foreign policy. These measures aim to protect domestic industries from what the US government perceives as unfair trade practices, global excess capacity, and imbalanced trading relationships. The policy includes mainland China, delayed […]

-

Insurtech: Tech predictions for the insurance sector in 2025

- January 27

2024 was the year we saw signs that the insurance industry is rapidly transitioning from experimenting with generative AI (GenAI) to deploying scaled production use cases. Fuelled by new data streams and advancements in IOT, and wearables, predictive capabilities are reaching new heights. However, prediction alone is insufficient to reduce loss ratios systemically; meaningful impact […]

-

2004 tsunami: Loss, and lessons: reckoning with the Indian Ocean tsunami 20 years on

- December 20

Though two decades have passed, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami is still fresh in my memory. I was in Australia at the time. It was a warm summer’s day, with many people starting to watch the Boxing Day test cricket match between Australia and Pakistan in Melbourne, when the news first hit. Like all of […]

-

Allianz General | Allianz General combines innovative protection solutions while powering social good to lead Malaysian market

The insurer proactively addresses emerging risks and evolving customer protection needs while giving back to the community.

-

Sedgwick | Asia’s Energy Transformation – Balancing Growth, Risk and Renewables

Energy market presents unique risks, especially in a region which includes China and Japan as well as developing nations like Vietnam and the Philippines.

-

Beazley | Turbulent Waters: the maritime energy transition challenge

Businesses are facing a complex transition to non-carbon energy sources amid a push to achieve net-zero emissions for the marine sector by 2050.

-

Aon | Navigating shifts in the global and Asia insurance markets

Neelay Patel, Aon head of growth for Asia, says the market in Asia is at an ‘interesting stage of the cycle’.

Indira Gopalakrishna, Milliman

The third wave of microinsurance

Indira Gopalakrishna, Milliman